Avoiding 'Lap Of Honour Syndrome' in practice sessions

I was talking to one of my students about our tendency to play ‘safe’ things during practice sessions when I came up with the title of this piece. We’ve all been guilty from time to time of spending our practice time playing through the bits that we’ve already learned and mastered, enjoying the feeling of having conquered the technical aspects of them. This is what I mean by ‘lap of honour syndrome’ - it’s the same tendency as winners of important races running an extra lap around the stadium to receive accolades from the crowd watching.

However, playing through safe or successfully learned passages is not going to challenge us, bring our playing up to the next level or help us to learn a new piece. Practice with the intention of learning new material shouldn’t sound polished and finished. Those of us who don’t fall into the ‘super-genius' category will come across technical challenges or questions about performance that will slow us down and this is to be embraced. Only by tackling hurdles and looking very closely at them can we reach the next level of playing.

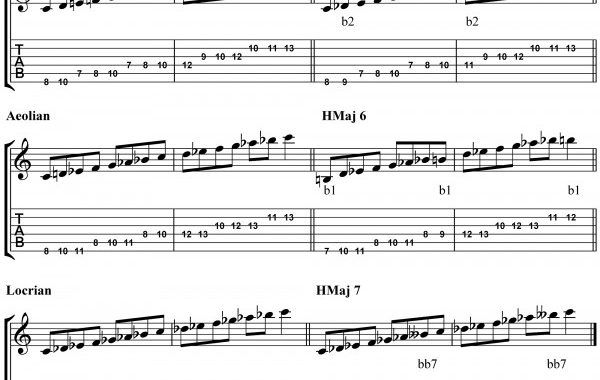

When I find difficult passages in a new piece, my first job is to study the notes and make sure they’ve been accurately read. After this I work meticulously on the fingering to plot the easiest and most accurate transitions from one phrase to the next. After this I break the passages down into short sections and start rehearsing them slowly. By slowly, I mean anything from 70 bpm to 40 bpm - I call it the ‘molecular’ level, because it feels like putting the music under a microscope. I may devise separate exercises to highlight a technical problem I’m wrestling with and build these into the practice. Only when I’m flawless at the slow speeds will I start to increase up to the medium speeds, but always keeping an eye on accuracy as I increase speeds incrementally.

Of course, doing this for too long can be very intense if you haven’t built up a tolerance for this kind of practice, so set times (with alarms if you like) for intense practice, but then finish off with the ‘reward’ of playing your favourite piece or doing your lap of honour with a piece that you've mastered previously. Once we get used to this type of practice though, we can practice smarter and not necessarily need the release of playing something easy or familiar at the end of our session. Experiment with it and see what’s best for you!

Happy practising!